Yama Farms Inn: A Home in the Mountains

Building Yama-no-uchi

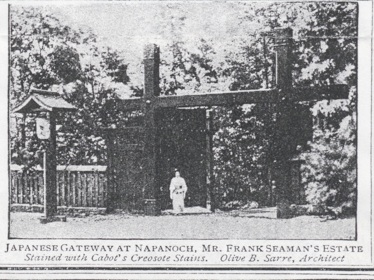

Olive Brown Sarre is generally acknowledged to be the designer of Yama-no-uchi. As described in a 1910 American Homes and Gardens article, this stunning Japanese-inspired complex “was entirely the work of an American woman.” Further testifying to Olive’s role is a 1915, advertisement in The Craftsman magazine. It depicts a portion of Yama-no-uchi with a caption beneath it reading “Olive B. Sarre, Architect.”

Work on Yama-no-uchi began in 1906 and was completed in 1910. The first structure to be constructed was an immense Japanese stable, the complex’s centerpiece. Local men removed over 1000 cartloads of cobblestone from Seaman’s property to use for the structure’s base. Unfortunately, the head stonemason was unable to follow Olive’s design, which called for gently curving support walls. In the end Olive had to remain on the site, standing over the crew, overseeing the placement of each stone. Local artisans, trained by Olive in traditional Japanese construction techniques, then erected a wooden superstructure above the stone base. The American Homes and Gardens article described it as “a large Japanese building of beauty and simplicity which fits its environing hillside with striking aptness.”

To local residents, the stables looked like a Japanese temple. For Clyde Lancaster, writing years later in The Japanese Influence in America (1963) the building was “like a Japanese castle.” Upon the stables completion, Seaman, pleased with “its fortress-like walls of rubble” pronounced the building “a great success—and an encouraging commencement of our project.”

The Stables

The Teahouse

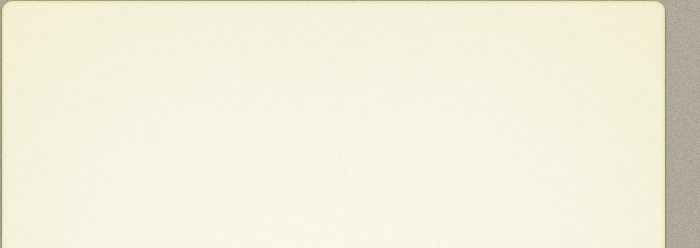

Waterwheel and Japanese-style structure that housed a turbine.

Stonemasons and other lcoal artisans trained by Olive Sarre in traditional Japanese building techniques constructed the buildings at Yama-no-uchi between the years 1906 and 1910.

Sarre repeated her cobblestone base construction at two other buildings erected at the complex, a teahouse and a small building that housed a turbine, an overshot waterwheel and a pump. The latter structure, framed by drooping willows, also featured an Asian-style roof with upturned corners. Like the stables, the super-structure of the teahouse was built with native chestnut. American Homes and Gardens (1910) was enthusiastic in its praise for both the building and Sarre:

“That Mrs. Sarre was able to build this exquisite tea-house practically without the driving of a nail, using the Japanese joints and wood pin methods exclusively and employing only ordinary American village carpenters is perhaps adequate tribute to her ability, though there are a hundred other evidences of it throughout this estate.”

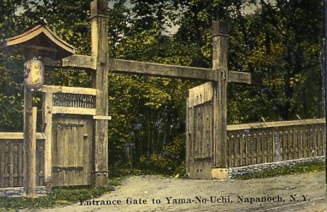

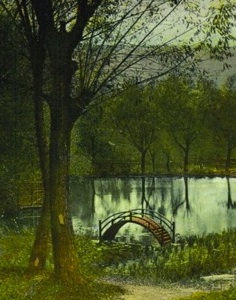

Entrance to Yama-no-uchi was through a Japanese gate with doors of solid wood, each ten feet high and hung on wrought iron hinges. Ideograms reading “Yama-no-uchi” adorned both a large lantern and the 12-foot high lantern stand that supported it. Once inside Yama-no-uchi, a series of walkways and roads guided the visitor through Japanese-style gardens that surrounded the five trout ponds. Near the center of the gardens, beneath the teahouse, Olive had placed an arched bridge and had it painted a deep red. The Sacred Bridge spanning the Daiya River in Nikko, Japan was said to have been its inspiration. According to Carlyle Ellis, the rare crimson lacquer used on the bridge had been obtained by Olive during her travels:

“….there is but one family in all Japan that makes the lacquer and has been making

it for four hundred years. It is manufactured only for the Nikko Bridge. The honor

is great.”

The Stable was considered the centerpiece of Yama-no-uchi. The massive yet graceful walls were composed of coursed rows of rounded glacial cobblestones, quarried from the surrounding countryside. Olive Sarre designed it and oversaw every detail of its construction. Clay Lancaster, author of The Japanese Influence in America (1963) likened it to a Japanese castle.

Clay Lancaster, author of The Japanese Influence in America (1963), pronounced the teahouse “one of the most faithful reproductions of Eastern building forms here.” Sited dramatically upon a steeply sloping hilltop, it was said by Travel Magazine, (1913), to have been built without the use of a single nail.

The lower entrance gate

Views of the arched bridge known as the “Moon Bridge” or “Nikko Bridge.” It was painted with a rare crimson lacquer that Olive Sarre obtained in Japan. Standing on the bridge are Loren and Ruth Shull, children of L. Huber Shull, overseer of poultry farm operations at Yama Farms. Upper Left Photo Courtesy of Roger Shull.

This advertisement, appearing in a March 1915 edition of The Craftsman

magazine, credited Olive Brown Sarre as the “architect” of Yama-no-uchi, thus providing additional evidence that she was the designer of the Japanese-influenced component of Yama Farms. Courtesy of William Rhoads.